By Ben Nwosu & Ndu Nwokolo

The Benue State of Nigeria is perhaps as unsafe as any severely terrorised territory. That valley of green vegetation that correctly prides itself as the nation’s food basket appears to have become a valley of blood flowing from constantly marauded agrarian communities. It is indeed one of the most persistent violence related to contestations for livelihood. It is estimated that between 2015 and 2023, herders have killed 5,138 farmers in Benue State.

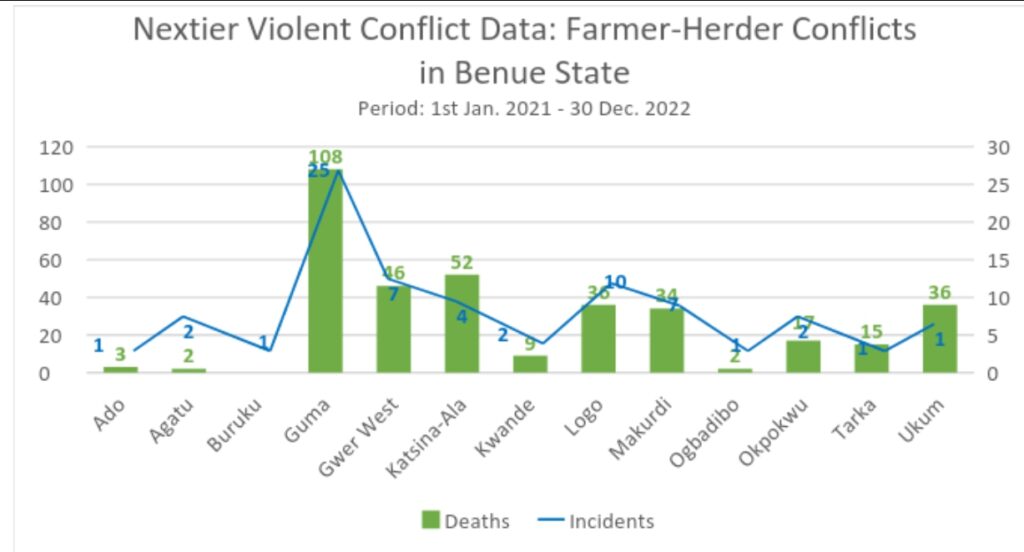

A few outstanding incidences of attacks with mass murder include that of the Agatu community in 2016, in which about 300 lives were lost. The Agatu attack, according to a Fulani leader, was a reprisal against the killing of one Shehu Abdullahi of the Fulani stock and carting away of over 200 cows from his house in April 2013. There was also the invasion of Logo and Guma Local Government Areas on new year’s Day of 2018 which led to the killing of about 70 persons. Just one month ago, in April 2023, another attack in Mgban and Otukpo Local Government Areas led to the death of 74 persons.

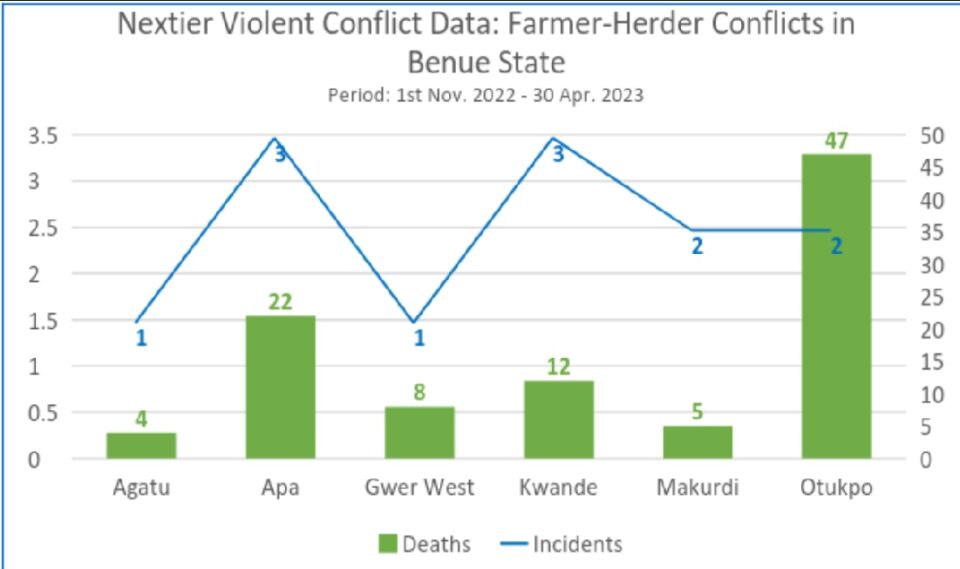

Over six months from November 2022 to April 2023, the Nextier Violent Conflict Database reports 98 deaths in Benue State in farmer-herder conflicts alone. The implication of this violence includes not only the depopulation of communities with constant killings but also forced abandonment of ancestral homes, expansion of the camps of internally displaced persons in the State and inability to cultivate the land due to well-founded fears of attack. Apart from the looming food insecurity from this crisis, the displaced communities are forcefully occupied by their attackers.

Reinforcing the whole climate of terror from agrarian violence is the learned helplessness of the government in the presence of the long-running carnage and population displacement in Benue State. The State government is obviously hampered due to constitutional limits of sub-national governments on matters of security and control of security apparatuses. In moments of desperation and helplessness, the Benue State Government had openly accused the Buhari-led Federal Government of treating the tragedy with indifference and connivance with the Fulani herdsmen who were behind the attacks. Thus, in its bid to provide security in some of its communities, the Benue state government August 2022 inaugurated its Community Volunteer Guards, with the main arm of providing conventional security in most of its rural agro-communities that are constantly under attack. Overall, the poor official response to the attritional violence supports its continuity and the festering insecurity in the Benue Valley. On that note, this edition of Nextier SPD Policy Weekly reflects on the conflicts in Benue State and the attitude of the state authorities that verges on learned helplessness.

* Learned Helplessness as an Official Attitude

Learned helplessness, in psychology, refers to a mental state of subjects who, out of constant exposure to adverse outcomes, become conditioned to see such outcomes as uncontrollable or normal even where they are not. For instance, when a dog is constantly exposed to electric shock, it would eventually stop reacting against exposure to such stimuli in contrast to another dog which experiences the same exposure for the first time and gives a prompt backlash. In this essay, we assume that the subject of such exposure is the government because it is also an entity that responds to social stimuli.

The logical expectation from a state when citizens are exposed to insecurity is that it deploys its apparatuses not only to protect the persons under menace from the immediate source of danger but also to put measures in place to degrade the source of the present danger and its future occurrence. Fulfilling this task is the reason for the existence of government. However, in the Benue State case, there is a worrying security gap occasioned by insufficient government intervention, especially from Abuja.

* Sources and Persistence of Violence Versus Response Gaps

The conflict in the Benue Valley has a long history but started its early manifestations in the immediate post-independence era. However, it became worse with the increase in climate change, which has caused increasing desertification and drying up of major hydrological resources that sustain the livelihood of herders. Lake Chad stands out among such resources threatened by climate change. Consequently, the cyclical movement of herders down to the Benue Valley during the dry season became a unidirectional movement in which herders no longer return to the Sahel region after the dry season. Conflicts became more common between Fulani herders and farmers with the increasing need for grazing land and trespasses into farms.

The conflicts were also deepened by the conflicting position of the constitution on the legal rights of citizens for freedom of movement and land tenure legislation which vests land ownership on the State and yet recognises cultural claims over land, on the other hand. Thus, each group embraced the aspects of the law that suited its interest and made bold claims about the right to use land resources. The conflicts became intense due to its ethnic slant as herders are mostly Fulani while the crop farmers are the indigenous communities of Benue State.

Minor conflicts of the earlier years of the interaction between herders and farmers boiled over in 2016 when the Agatu killings occurred. The Federal Government, which exclusively controls the armed security services, intervened through a presidential directive to set up a panel of investigation and an inter-agency security team to forestall further attacks. These measures yielded little solution as the carnage persisted. Besides, the soldiers sent to the community were accused of brutality in some of their operations.

In response to continuing violent attacks and the destruction of crops, the Benue State government enacted an anti-open grazing law in 2017 to prevent the unrestricted movement of cattle and its attendant damages. This law was not well-received by the herders, and it no doubt added to the tensions, which were already at a high level in spite of its good intentions.

Another landmark attack in which 70 persons were killed took place on January 1, 2018. The Federal response to this violence included the President’s commitment to the Benue State Governor to protect farmers and communities. Also, there was a presidential directive to the Inspector General of Police to relocate to Benue and a stakeholder meeting by the Inspector General of Police with the elders, community and religious leaders. Equally, there were deployments from different teams of the police force with special equipment, including aerial surveillance helicopters. In addition, special forces from the military were deployed in the State, and eight suspected herdsmen were arrested in relation to the attack. While the above steps appear robust, the result, which is the end of attacks on farmers by marauders, did not stop.

Due to the continuing conflicts, an estimated 1.5 million persons are in Internally Displaced Person camps in Benue State with varying degrees of health challenges and hunger. In the face of these human catastrophes, another attack involving the death of over 70 persons occurred in April 2023. The response from the Presidency over the attack was a blame on the State Governor for leadership gaps.

The Benue State Government tasks the Federal Government to undertake a realistic intervention in the conflicts because that level of government controls the security services. The Federal Government fails to be swift, decisive and result-oriented in its interventions. In fact, the reports of mass murder in Benue and other states of the country have become so commonplace that it is taken to be a normal occurrence in the country. Security institutions of the State, being under multiple burdens, are getting over-stretched, which may account for their suboptimal performance in stopping marauders. Above all, there is a conspiracy theory that the security institutions of the State are not neutral in the conflict and therefore feign incapacity or helplessness in responding to the attacks.

* Recommendations

In light of the government’s lack of decisiveness in dealing with the persistent attacks on communities, we recommend as below:

National institutions involved in managing the conflict in Benue and other states should be given thorough training on loyalty to the country’s constitution, even at the risk of disobeying powerful political interests that wish to project and pursue narrow, provincial interests.

Sequel to number one above, the training should be extended to all security institutions of the country on the need for loyalty to the constitution and national values, not to narrow regime interests.

The frequent violence in Benue and some other states of the country and the increasing pressure it entails for the country’s security institution suggest the inevitable need to reorganise the national security architecture to include more local participation. In other words, there should be conversations about more robust local policing and the nature it should take.

There is a need to build local intelligence and early warming responses around Benue Community Volunteer Guards and other local non-state security outfits in order to respond to some of these attacks before they occur. Therefore, a synergy between formal (National security outfits) and semi-formal (in this case, state-governments-supported policing outfits) should be given serious consideration. Any security architecture that is not driven by local intelligence and knowledge may not likely be successful.

* Policy Recommendations

National institutions involved in managing the conflict in Benue and other states should be given thorough training on loyalty to the country’s constitution.

Training on loyalty to the constitution and national values should encompass all security institutions.

The national security architecture should be reorganised to include more local participation as it pertains to a more robust local policing and its nature.

There is a need to build local intelligence and early warming responses around Benue Community Volunteer Guards and other local non-state security outfits in order to respond to some of these attacks before they occur.

*Conclusion

The agrarian violence in Benue State appears intractable. The reason is that state security institutions that should stop the conflicts are hampered by vested interests in government, which fails to permit the security forces to be guided by the constitution and ethos of service to the national interest. Consequently, mass killings occur with impunity while the governmental institutions fail to act not for lack of capacity but for narrow regime loyalty. In the process, the government appears like a subject conditioned into learned helplessness while its citizens are constantly exposed to the danger of mass murder.

(Dr. Ben Nwosu is an Associate Consultant at Nextier SPD, a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Development Studies, University of Nigeria, while Dr. Ndu Nwokolo is an Honorary Fellow at the School of Government and Society at the University of Birmingham, UK.)