Nigeria’s northeast region has faced extensive terrorist violence for over twelve years. Several communities in the region experience terror attacks that have degraded livelihood opportunities, exacerbated poor services and deepened the humanitarian crisis.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations’ Nigeria Security Tracker, about 35,000 people have died from the ongoing crisis. Over 2.5 million people are displaced within the region and in the Lake Chad Basin. Data from Nextier Violent Conflict Database show that between January and March 2022, the region recorded 23 violent conflict incidents resulting in 172 deaths and 23 kidnap victims.

Compared to the same period in 2021, the region recorded 35 percent more violent incidents, a 91 percent increase in deaths, and a 109 percent increase in the number of kidnap victims. This violence trend may endure as many of the region’s population are vulnerable to new attacks despite the counter-terrorism measures of the Nigerian government and her Lake Chad Basin neighbours.

Trailing the northeast’s terrorist attacks are the displacement and humanitarian woes. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) seek refuge in displacement camps where basic services are sparse, coupled with limited opportunities for livelihood and self-sufficiency.

The humanitarian crises spill beyond the IDP camps to include communities, where large populations struggle due to depleted livelihood sources, destroyed infrastructure, bodily harm, limited access to and availability of external support. Such host communities are often hostile to the IDPs, given that available resources cannot meet the needs of both groups. Furthermore, beyond the communities that have been sacked by violence, other residents face the direct and indirect impact of the northeast violence.

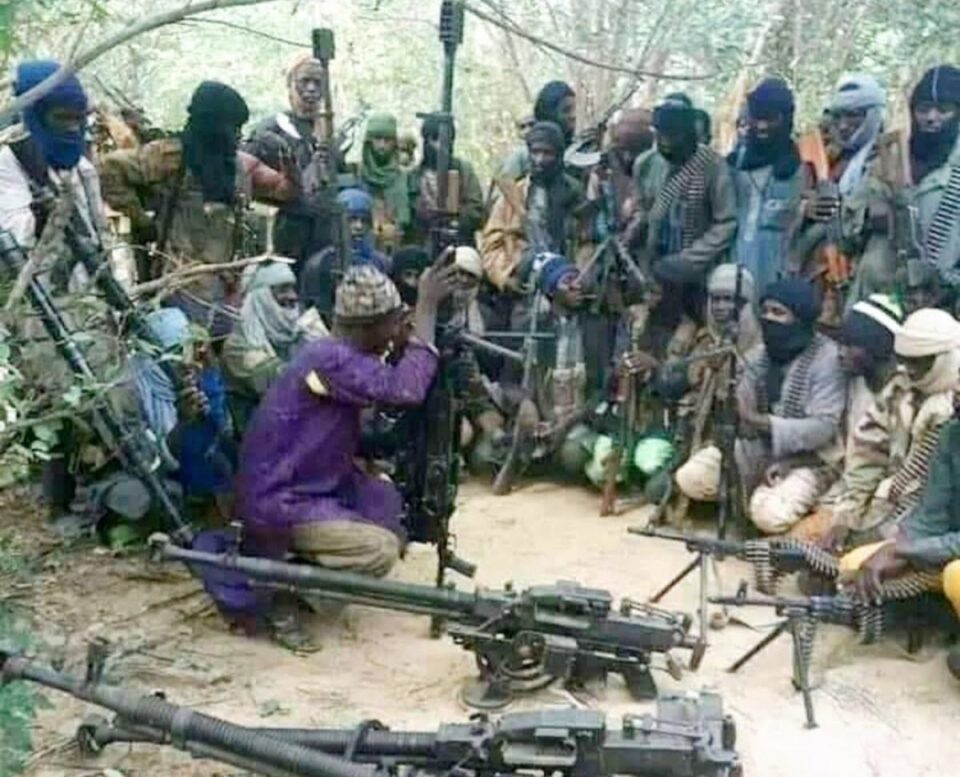

Women, girls, and boys significantly populate refuge sites in Nigeria’s conflict-impacted northeast and beyond it. These demographics’ vulnerabilities are deepened by the continuance of terror, prolonged displacement periods and humanitarian crises. Besides, most violent conflicts affect women and girls differently. For instance, women and girls in the northeast are often kidnapped, sexually violated, forced into marriages, or turned into suicide bombers. Young boys are victims of these challenges as their vulnerability predisposes them to the antics of jihadist groups.

Furthermore, boys in this situation are also recruited by self-defence militias. In 2018, the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) reported that a local militia fighting Boko Haram insurgents released about 833 child soldiers in northeast Nigeria. According to UNICEF, the released children were among the nearly 1,500 boys and girls recruited by vigilante militias.

The Nigerian government and its development partners strive to assist the afflicted populations. Efforts are also made to return and resettle millions of the displaced population. The resettlement, therefore, includes empowerment schemes that should promote self-sufficiency.

Beyond the focus on affected populations, the Nigerian government opened an amnesty window in 2016 for low-risk repentant insurgents. The Nigerian military’s Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) manages this programme as a counter-insurgency approach to deplete terrorist organisations in the northeast and broader Lake Chad Basin.

However, reintegrating processed participants of the programme has proven difficult as many communities say they do not want them back.

The conflict in the northeast and its aftermath have depleted social cohesion. Multiple subsets of the population have been created as a result. Fostering social cohesion between the groups has been difficult for the Nigerian government.

For instance, several intervention programmes in the region have a social cohesion component, given the subject matter’s relevance to community resilience and stabilisation. Social cohesion is also relevant to preventing and managing internal conflicts such as the indigene-settler dichotomy, IDPs versus host communities, repentant insurgents, and host communities. These scenarios require a more robust and all-inclusive engagement to salvage multidimensional challenges.

The development challenges in the northeast region are significant but not intractable. The Nigerian government must encourage its development partners to support intrinsic community efforts geared towards resilience. Nextier recently completed a study on community conflict resilience in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states.

The study, funded by the Managing Conflict in Northeast Nigeria (MCN) programme, highlighted several homegrown resilience solutions. The resilience initiatives include shifts in gender roles, cultural and religious practices, the use of sporting activities, and the involvement of more women in agricultural and economic activities.

Nigeria’s Northeast Development Commission and the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development should integrate such community-led solutions into their toolkits.

The government should make more coordinated efforts at all levels to manage humanitarian interventions in the region. The federal government must drive efforts to synergise the roles of relevant stakeholders working in the conflict zone for sustained impact. Such limited coordination reflects a duplication of efforts from the various stakeholders.

Recommendations from the same study mentioned above recommended that the government make a more coordinated effort to manage humanitarian interventions in the region effectively. This recommendation calls for effective synergy among the various disaster management partners in the northeast region: the government, non-governmental organisations, development agencies, and community-based associations.

Securitisation is a critical factor in community conflict stabilisation. Government must strive to govern ungoverned spaces, securitise the violent hotbeds and prevent the infiltration or takeover of communities by insurgents.

These goals can be achieved by re-establishing government presence in rural areas through security deployment, providing basic services, and maintaining law and order. Furthermore, securitisation efforts in the region should involve efforts to increase the engagement of local actors in understanding the conflict dynamics and generating local intelligence.

Nigeria can’t make significant progress in the region, with about 8.4 million people still requiring humanitarian assistance, coupled with the unending violent attacks by insurgents. There is a need to engage in a holistic approach to end the insurgency and manage the humanitarian crisis.

Additionally, the region’s displaced and embattled population require serious support to rebuild their lives and achieve self-reliance. Nigeria’s northeast region requires multi-layered but coordinated interventions to address its multidimensional challenges.