Protecting valued assets and maintaining law and order are some core essences of state formation. Such valued assets include human and infrastructural assets and the state’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Also, state and human security entail the absence of fear that valued assets will be attacked and the pursuit of freedom from want and fear (Thomas and Aghedo, 2014).

For over two decades in Nigeria, violent insecurity has surged in scale and sophistication, posing an unprecedented threat to valued assets, including lives, investments, and the state’s territorial integrity.

In this report by Nextier, a leading think tank in Nigeria, experts assert that statistical mapping based on the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data and Nextier Violent Conflict Database reveals that between January 1997 and March 2020, 2,203 incidents of hostility between and among ethnic-based militia groups resulted in 16,328 fatalities. For the same period, 1,473 incidents of pastoral banditry killed no fewer than 9,971 persons (55 per cent from 2015). Between 2000 and 2018, 19,896 cases of pipeline vandalisation and 320 cases of rupture were recorded in the Niger Delta, resulting in the loss of 2.45 metric tons of oil worth 125.4 billion Naira and 375 fire outbreaks (Oyewole, 2021).

The experts argue that between 2000 and 2019, the Gulf of Guinea region recorded 987 piracy and armed robbery against ships (52.6 per cent occurred in Nigerian waters). In addition, between 2009 and March 2020, Boko Haram and its different factions were involved in 3,283 incidents of armed conflicts, claiming 33,127 lives in Nigeria (Oyewole, 2021).

More recently, between January 2021 and April 2022, 6,961 murder cases were recorded in the country (6,895 in 2021 alone). Besides civilians, state security personnel continue to pay the supreme price. For example, between January and April 2022, 158 security officers were killed (Nextier Violent Conflict Database). Efforts by scholars and policymakers to explain and mitigate violent insecurity have been wide-ranging, although with little success. They have highlighted some driving factors such as Nigeria’s youth bulge, arms proliferation, high unemployment level, mass poverty rate, the politicisation of security agencies, poor funding of security agencies, and poor use of Information, Communication, and Technology in policing crime and violence, etc. While these explanations are compelling, little attention has been given to Nigeria’s need to strengthen community policing as a mitigation strategy.

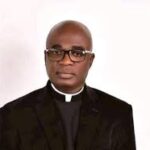

As a result, this edition of Nextier SPD Policy Weekly examines how the powers and functions of the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) can be sufficiently devolved to the community levels to enhance optimum performance. The report is authored by Dr Iro Aghedo, an Associate Consultant at Nextier SPD and a Senior Lecturer, Department of Political Science, University of Benin, Edo State, Nigeria, and Dr Ndu Nwokolo is a Managing Partner and Chief Executive at Nextier SPD and an Honorary Fellow, School of Government and Society, University of Birmingham, UK.

On the issue of discontent over centralised policing, the Nigeria Police has been a national institution since it was established in 1820 as a principal law enforcement and security agency by the British colonial masters. The Nigeria Police was federalised in 1930 when the Northern and Southern police forces merged. Between 1999 and 2016, four police reforms were undertaken by different administrations, but they were not implemented. In August 2020, President Buhari, following a National Economic Council decision, approved the sum of ₦13.3 billion to launch the Community Policing scheme, with the aim of rejigging “the security architecture in the country and delivering a more effective policing” (FES/CISLAC Policy Brief, 2020:8).

Under the scheme, 10,000 police constables were recruited, trained, and deployed to their catchment areas. However, this planned reform became a contention between the Police Service Commission, the Nigeria Police Management Team, and some state governors.

Thus, the reform has remained unimplemented, making the 371,800 staff of the police working in 17 Zonal Commands, 37 State/FCT Commands, 128 Area Commands, and 1,388 Divisional Commands, and 1,579 Police Stations federalised (FES/CISLAC Policy Brief). Police operatives at the zonal, state and divisional levels take ultimate instructions from the top echelon of the NPF in Abuja. Even though state governors are said to be the chief security officers of their states, the police commissioners in the respective states do not take instruction from the governors. Despite this anomaly, state police commands still receive enormous financial and logistical support from state governors in a clear case of ‘funding without authority’ by state governors.

This federalisation of the NPF is not in line with global policing best practices that underscore the devolution of functions to security communities at the grassroots, as currently done in the United States, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and India, among others.

The centralisation is also inconsistent with the spirit of federal practice. Furthermore, the centralisation of the NPF is at variance with the dynamics of insecurity in the country. Crime and violence have become sophisticated in recent years.

For example, many militants, insurgents, bandits, and terrorists now occupy and use ungoverned Nigerian forests as their bases. Yet, federal police operatives deployed from one state to another are unfamiliar with the geography, terrain, culture and even language of the areas they are posted. The frustration and unfriendly police-citizen relations arising from working in unfamiliar environments often lead to extortion, corruption, human rights violations, and extra-judicial killings by the police (Personal Communication). If persons from local communities were allowed to police their areas with some degree of oversight, they would be more effective because they are familiar with their environment, terrain, and other local peculiarities (Personal Communication). This played out in the North-East when members of the Civilian Joint Task Force proved very useful when they collaborated with state security personnel in the war against terrorism (Agbiboa, 2015).

On the Imperative of community policing, It is obvious from the escalation of violent insecurity in Nigeria that the extant heavily centralised security architecture is not pragmatic. Therefore, there is a need to restructure and decentralise the NPF to make it congruent with modern-day security realities and the practice of federalism.

The following policy measures are important in reforming Nigeria’s internal security architecture.

1. Standardisation of community vigilantes: Globally, the practice of ‘policing beyond the police’ (that is, extending policing functions beyond formal police institutions) has become a norm, especially in the post-9/11 era, as security has become the responsibility of all citizens. More community actors have been made to play policing roles, including private security guard companies. In line with the concentric circles model, Nigerian communities should be assigned policing roles at the grassroots where the people are conversant with the local environment, forests, waterways, cultural practices, and language. A starting point for this is the careful recruitment, training and standardisation of community vigilantes.

2. Effective coordination of non-formal regional security groups: Across Nigeria, some regional non-state security groups currently operate at the grassroots. Such groups include the Hisba in parts of the North-West, Civilian Joint Task Force in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states in the North-East, Western Nigeria Security Network (code-named Amotekun) in the South-West and Ebubeagu Security Network in the South-East. For now, these groups operate with little or no formal recognition by the federal government and the NPF. Yet, they play critical policing roles in intelligence gathering, crime control, and violence mitigation across their regions.

3. The need for oversight: to avoid possible abuses such as human rights violations and misuse by the local political elite, the NPF should exercise effective oversight over the vigilante and regional non-formal security groups. Rather than antagonising the NPF and the federal government, these groups should be coordinated and given the necessary financial and logistical support to upscale their performance. These non-conventional security actors must be integrated with conventional law enforcement institutions, maintaining oversight of the former. There is a need for concessions and accommodation rather than exclusion and domination in national security architecture.

4. The need for legislation: Obviously, changes to extant internal security architecture will require legislative amendment. For example, the structure, organisation, membership, powers, authority, arms possession, etc., of the vigilante and non-state regional security groups need to be statutorily defined and codified. Besides, the relationship between the groups and the NPF must be statutorily specified. Thus, necessary constitutional amendments will have to be made to the Police Act and other laws to accommodate the decentralisation of policing functions to the community levels.

CONCLUSION:

The rising crime rate, sophistication in the levels of violent insecurity and the poor response of the NPF to the internal security threats show that the functions of the centralised state security institution need to be devolved. As the norm in the post-9/11 era, policing beyond the police has made community policing a global practice. As argued above, the federal government and the NPF need to make some concessions and integrate credible unconventional vigilante groups and regional security actors into the conventional police. Surely, the integration will require amending some extant laws, such as the Police Act.

REFERENCES: Agbiboa, D. (2015). Resistance to Boko Haram: Civilian Joint Task Forces in North-Eastern Nigeria. Conflict Studies Quarterly, 3-22.

Oyewole, S. (2021). Struck and Killed in Nigerian Air Force’s Campaigns: Assessment of Airstrikes Locations, Targets, and Impacts in Internal Security Operations, African Security Review, 30 (1):24-47. Thomas N. A. and Aghedo, I. (2014). Security Architecture and Insecurity Management: Context, Content, and Challenges in Nigeria, Sokoto Journal of the Social Sciences, 4 (1): 22-36