By Chesa Chesa

The unrelenting theft of Nigeria’s crude oil, that cost the nation no less than $3.5 billion in 2021 alone, has again been thrown up for debate and solutions sought.

The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) previously announced a loss of $159 billion due to oil theft and pipeline vandalism in 2019. According to recent figures, oil thieves take up 95 per cent of Nigeria’s oil production.

It has been gathered that despite rising international oil prices, NNPC Limited failed to remit its mandatory funding to the Federation Account in January 2022, while in February 2022, it deducted ₦383.09 billion from the oil and gas revenue due to Nigeria’s Federation Account.

These deductions were for Joint Venture (JV) strategic holdings, pipeline operations, and other costs that resulted in the non-remittance to the Federation Account.

Besides, according to a credible source at the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), NNPC Limited has not remitted any money in the last five months, and there are more trying months ahead.

Already, Nigeria has resorted to borrowing, with the Debt Management Office reporting that Nigeria’s total public debt stock increased from ₦32.92 trillion in 2020 to ₦39.56 trillion in 2021.

Noting these issues as existential economic threat, think-tank group, Nextier, convened a session during the week, during which industry experts took turns to interrogate oil theft, including challenges and prospects available to change the situation.

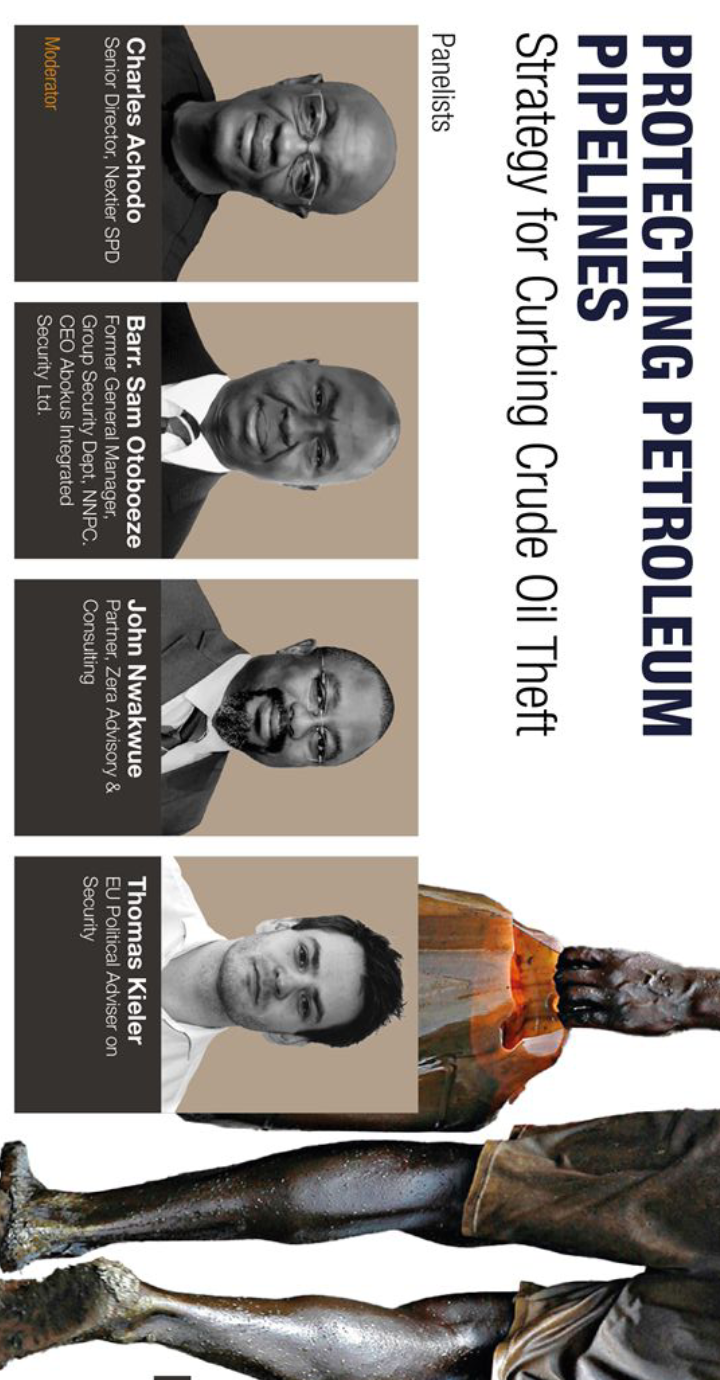

The dialogue, which held virtually with the theme “Protecting Petroleum Pipelines: Strategy for Curbing Oil Theft in Nigeria”, drew participants and panelists from the oil sector within and outside Nigeria.

There were notable names like Barrister Sam Otobueze, former General Manager/NNPC Group Security; Joe Nwakwue, Petroleum Sector Specialist and Partner, Zera Advisory; Thomas Kieler, Political Adviser on Security to the European Union Delegation in Nigeria; and Charles Achodo, Senior Director at Nextier.

In his presentation, Nwakwue worried that losses associated with oil theft have continued to rise. According to him, Nigeria’s oil production in 2021 averaged about 1.6 million barrels but has reduced to 1.2 million barrels in 2022. This means that Nigeria has an idle economic capacity shortage of about 700,000 barrels per day.

Speaking about the investment potential in Nigeria, he outlined numerous reasons investors may be hesitant to engage in Nigeria’s oil business.

According to him, when considerable volumes are lost, the technical unit cost of manufacturing rises, making enterprises less profitable. “If the investor has a re-payment timeline and no volumes to meet, the scenario becomes considerably worse”, he stated.

Commenting on the lack of development in the Niger Delta, Nwakwue asserted that no part of Nigeria is developed.

“Rather than give the benefits directly, we have created artificial entities called unaccountable states. Huge sums have been devoted to developing the Niger Delta, but intermediaries at the state level have diverted these resources”, he said.

According to him, people are stealing crude because they are thieves, not because of hunger or underdevelopment in the Niger Delta region.

Nonetheless, Nwakwue pushed for the adoption of technology such as the Kimberly process or fingerprinting for each export grade, even as he advocated for international cooperation to combat global oil theft.

On his part, Sam Otobueze regretted that the rise in oil theft portends doom for Nigeria in the coming years, citing that oil and gas account for 89 per cent of Nigeria’s national income.

He also noted that the exponential population growth triggers increased insecurity as resources to care for citizens become scarcer. He further stated that it was easier to make laws than enforce them.

“Making law in the face of hunger may prove impotent”, he said and advised the engagement of relevant stakeholders and gaining community buy-in in implementing laws on pipeline protection.

Otobueze further highlighted that it was impossible to anticipate or demand local population involvement in pipeline security until the gains are shared equitably with the locals.

Thomas Kieler observed misconceptions about the structure of criminal groups involved in oil theft, as he argued that oil theft and illicit bunkering are not limited to small artisanal organisations but involve highly organised criminal gangs.

He was perplexed as to why Nigeria finds it difficult to follow the Saudi Arabian pipeline monitoring model.

In response to inquiries about the probable drop in sea piracy, Kieler stated that the Niger Delta region had a significant presence of naval assets that cause deterrence.

According to him, there are five European naval assets from Denmark, France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal in the Gulf of Guinea.

The Nigerian Navy and the Nigerian Maritime and Safety Agency (NIMASA) has also upped their operations; while a new anti-piracy law was passed in 2021, resulting in the conviction of ten pirates so far.

Kieler further stated that efforts in curbing the challenge of curbing oil theft in the Niger Delta could take the short, medium- and long-term dimensions.

He described the short-term plan as “securing the region and defending pipelines,” with the medium-term plan being “law enforcement and identifying financers.” The most difficult yet beneficial is the long-term arrangement that involves the host communities in important decision-making and livelihood processes, he posited.

To avoid what he termed “the balloon effect”, Kieler further recommended that attention be given to long-term objectives such as empowering and sustaining impacted communities. He also argued that criminal organisations keep reinventing themselves because the core concerns of the populace are neglected.

Dr. Ndubuisi Nwokolo, Partner at Nextier, in his presentation noted the ‘moral economy’ dimension to the challenge, by which some justify the theft of Nigeria’s crude oil. According to him, every indigene in the Niger Delta who steals oil can claim moral standing.

He also described the issue in terms of the greed-grievance ideology, in which people desire to transition from being offended to becoming greedy for their share. In this case, oil thieves in the Niger Delta react to how the state and political class have treated them.

Dr. Nwokolo disclosed that Nextier would facilitate stakeholder engagements with community leaders, implementing partners, oil companies and other stakeholders to further discuss the best way to end oil theft.

In addition, he canvassed for greater awareness and media publicity for people to become aware of the dire consequences of bunkering and illegal oil theft in Nigeria.